Samuel Beckett’s 1973 play Not I is barely 16 pages long. In it, the stage is dark except for a tight spotlight on a woman’s mouth some 8 feet above the stage. Mouth (the only name she’s given) babbles, laughs, screams, sometimes even falls momentarily silent. The story she tells, in fragments with barely a single complete sentence among them, is of a lonely and isolated life: parents who vanished early, a childhood in an orphanage, some sort of punishment, a court case, and being all but speechless until a sudden flood of words very late in a long life. All this is told in the third person. Occasionally, Mouth seems to be responding to some sort of question from elsewhere. On four occasions, she stops and insists vehemently on the third person (“… what? … who? … no! … she! ..”). On those occasions, a dimly seen Auditor clad in a hooded djellaba downstage left responds with “simple sideways raising of arms and their falling back, in a gesture of helpless compassion,” each one less than the one before, and the final one barely perceptible. The words of the title are never spoken.

Third-person is a defence, and the only one left. Who did all of this happen to? Someone else: not I.

This may be rather useful for thinking about one important aspect of what’s happening in Finnegans Wake. Not I is an intense distillation of something central to the Wake, and which is going to become a focus in chapter I.2.

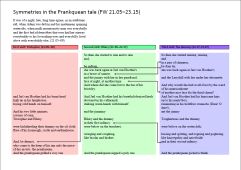

On the first page of the book, long before anything else in recorded history, we have the sleeping giant spread out across Dublin. There’s no first person here, or even really anyone for it to happen to, just a vast, inert, profoundly unconscious body, with its head at Howth and its toes in Phoenix Park. Over the page, we are immediately plunged into all sorts of dark and barely comprehended conflicts, which would suggest that this is at very least a troubled sleep. Out of these conflicts, a succession of figures emerges. First of all, there’s “Bygmester Finnegan, of the Stuttering Hand” (4.18), who also seems to be called “Wassaily Booslaeugh of Riesengeborg” (5.5-6). That he’s “like Haroun Childeric Eggeberth” (4.32) and “He addle liddle phifie Annie hugged the little craythur” (4.28-29) will in retrospect tie this Finnegan to HCE and ALP, neither of whom have yet arisen except in those trigrams. And as this Bygmester Finnegan is a builder engaged in building something like the tower of Babel, it’s hardly surprising that proper names, like everything else in language, should be sliding around a lot here. He’s also, already, part of a repetition: “Hohohoho, Mister Finn, you’re going to be Mister Finnagain!” (5.9-10). No sooner are we introduced to him than he’s gone again, dead, fallen off his wall, and we’re reminded again of that “brontoichthyan form outlined aslumbered” (7.20-21). Kate shows us through the Waterloo museyroom, and we’re introduced to another avatar, the Willingdone: this time it’s not just an accident that leads to his demise, but the plotting of the sons. We find echoes of the same figures in the old chronicles (13.33-14.15). We get another version of him with Jarl van Hoother and the story of the Prankquean, which offers an explanation of how the sons got turned against the father. And then we’re back at Tim Finnegan’s wake again, with the corpse aroused by spilt whisky, and apparently greatly disturbed by certain mentions of his daughter and then his wife. The thing that finally seems to quiet the corpse down and lead to his slipping back into unconsciousness is the chapter’s final assurance that yet another version of him, his replacement HCE, is already on his way.

So, repeatedly we have a sleeper, disturbed by struggles that are not yet at all clear, and returning to unconsciousness not because the struggles are resolved in any way at all (or even fully expressed), but because they can be passed on to someone else, whose purpose is to bear these conflicts with the distance afforded by denial: not I. As Freud argues, one of the functions of a dream – if we do even have a dream here – may be the attempt to prolong sleep. HCE is thus in this sense not at all the sleeper, but a sort of alibi, a figure onto which all sorts of unsayable and even unthinkable matters can be displaced. HCE is at at least two removes from the sleeper, that silent and inert giant underlying everything: he’s at very least the replacement for a stand-in (Finnegan) – and in the course of getting there, we’ve also had those more fleeting stand-ins, the Willingdone and Jarl van Hoother. The name, perhaps, is warning enough. Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker? Really? (We should be no less suspicious of Anthony Burgess’s claim that the real waking name of this family is Porter: a publican called Mr Porter is like calling your butcher Mr Chops – or your two sons, a writer and a postman, Shem the Penman and Shaun the Post. They are, after all, and as the next chapter will say about HCE, occupational agnomens (30.3)).

HCE, then, is a screen onto which deeper worries and fears get projected, a screen on which they can be both brought to some sort of obscure light and at the same time denied: not I (because there’s no I here anyway), he. Because of this distance, HCE can be the object of the most fervent and repeated denunciation, as well as the object of an unabashed wish-fulfilling admiration, in rapid alternation but also, because of the incessant undermining the wordplay performs, sometimes even in the same sentence. The sheer onslaught of all this repetition, the sheer relentlessness and self-accusing ferocity of it, is a dimension that’s altogether missing from Campbell and Robinson’s A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake. For them, HCE is Everyman, an eternal and unchanging archetypal story that therefore is bound to repeat. What they miss in their Jungian reading is perhaps the genuinely Freudian dimension of drive: the way this story is repeatedly uncomfortable and mortifying, but for all that is powerless to stop itself, like the torrent of words from Mouth in Beckett’s play.