It’s a commonplace for Wake commentators, beginning with Campbell and Robinson’s Skeleton Key, to see the Wake as presenting us with a protagonist who is Everyman, whose dilemma is universal, recurrent everywhere and in every era. It appears to be an obvious way of treating the book: HCE is, after all, Here Comes Everybody, and the family’s trials and squabbles get mapped onto almost everything one can imagine in history. What could be more simple?

Nevertheless, it’s a view I’ve been finding increasingly inadequate. Here are some reasons:

- The statement that such-and-such a character or situation in a book is universal is a banality, not an insight. Rather than look carefully at the specifics of what’s happening in the book, it takes a large step back until the lack of detail makes the book look very broadly like lots of others. As the Wake says, “the farther back we manage to wiggle the more we need the loan of a lens to see as much as the hen saw” (112.01-02). To read from such a distance is to make everything that’s potentially new and challenging about the book dissolve into a familiar and simple story one already knows and has read many times before. The hero with a thousand faces turns out to have one face all along, which is the one he had in the last book.

- Presenting banality as discovery is bad lit crit. The claim that because one is familiar with something it must therefore be universal, or something as vague and all-encompassing as “human nature,” is also a deeply suspicious one to make in general. All it really says is that the speaker can’t imagine being otherwise.

- Is Joyce really writing 628 pages of some of the most difficult prose ever written in order to show a truism? (I’m using that word to mean something that appears obviously true if you don’t look too hard at it, and useless or just plain wrong the moment you do.)

- The argument that the story’s universality is shown by the 60-odd languages the Wake puns in and across also falls apart as soon as you look at it. They have quite the opposite effect. Nobody, even the “ideal reader suffering from an ideal insomnia” (120.13-14), is familiar with all those languages, from Shelta, Old Church Slavonic and Melanesian pidgin to Samoan, Turkish and Rhaeto-Romanic. Their effect is not to open the page up to a universal reader, but to guarantee that any actual reader experiences the Wake as devolving into opacities that are almost fractal. On those occasions when you do think you’ve made a certain amount of sense out of a passage, it’s a common experience to find that McHugh’s or Fweet’s glosses will identify it as a multilingual pun in a language you’re unable to pursue it through. Conversely, it’s a common experience to look up McHugh for a passage you find opaque, only to realize with a sinking feeling that the blank space means McHugh doesn’t know either. The experience of reading any text often present itself as a play of not-knowing and knowing, where the former seems to efface itself in favour of the latter. What the multilingual puns of the Wake guarantee is that not-knowing doesn’t fade out: it’s always in the forefront of the reader’s experience. We are always, and very often uncomfortably, aware that Wake language is simply not letting us plunge beneath the surface to some sort of familiar story beneath it. Surely we have to treat that opacity as in some way what the book is about, not something to be dissolved almost immediately in the assurance that it’s no more than an unusual or virtuosic way of conveying a universal story we already know.

- Campbell and Robinson focus almost entirely on the content of what’s said in the Wake (which of course is no mean achievement, and a major moment in Joyce scholarship). But they have very little to say about the act of saying it, and how that completely reframes the content. The points that follow are about some of the aspects and implications of this.

- Finnegans Wake is obviously excessive, but few texts are quite so excessive. If we simply look for the content, we find—over and over, and in all sorts of guises—the story of HCE, his family, his apparent misdemeanours, his guilt, and the desire for exculpation. It’s tempting to read this as universal, especially when the text itself is so full of statements to that effect. Maybe too easy. But when someone tells us something a little bit too often—especially when it’s something apparently obvious, banal and anodyne—don’t we have reason to suspect something’s the matter, just as the Cad becomes suspicious when his request for the time is met with an outpouring of protestations of innocence over some events he’d never even suspected before that point (35.01-34.36)? If something is really so obvious, so universally true, why say it at all, let alone over and over? And when the repeated assertion is that a particular action is no more than that usual suspect for all felonies, “human nature,” don’t we suspect that there’s a whitewash going on? Would we for a moment credit it if it were offered, for example, by that other well-known target of accusations of sexual misdemeanours, Harvey Weinstein?

- These excuses are also completely contradictory. The claim that whatever happened it’s a universal story, something that we find everywhere in history, sits ill with the equally frequent claim that nothing happened anyway. It’s what Freud calls kettle logic: (“When you returned the kettle I lent you, it had a hole in it.” “It was fine when I gave it back to you, the hole was already in it when I borrowed it, and I never borrowed it anyway.”) Any one excuse may or may not be true, but when they’re piled one on the other they give away a certain desperation. Very often, this is doubly marked by the stutter of the flustered and disingenuous HCE.

- Combine the contradictions with the excessiveness that comes from trying to plug all the holes only to find that your very efforts are making new ones, and what we have is a comedy of mortification. The long and sometimes mock-scholarly investigation of the letter in I.5 is a marvellous example of this. The letter the hen scratched up looks nothing like the exoneration it’s supposed to be: the comedy is in the increasingly desperate ways the narrative has of making out that it is, and that it couldn’t be anything else. Campbell and Robinson don’t have an ear for this comedy, which lies in the act of saying rather than the content of what’s said.

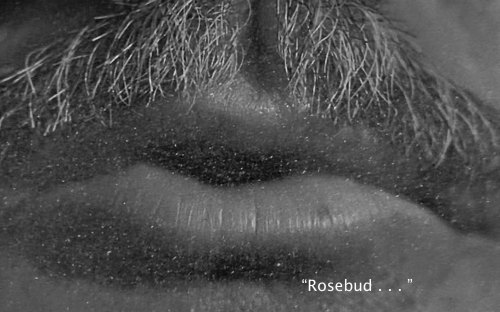

But classical narrative theory has lots of trouble with impersonal narration. Everywhere, it rushes to fill in the void by inventing personlike “narrators” who can be supposed to know, or see, what we are being told. It may be worth resisting this rush, to consider what might be at stake in the possibility of an impersonal dimension to narration. We have that, certainly, with Finnegans Wake, where there’s barely anything like an “I” to connect all of this to. But don’t we also have it already in, for example, the very common use of third-person narration focalized on one of the characters? Take A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, for example. Doesn’t the third person there work not as the point of view of some impossible, magical being with access to Stephen’s inner life, but as an aspect of Stephen himself, this proud, idiosyncratic boy and adolescent who is always viewing himself as if seen not quite by others (for whom he often has a complete disdain) but by the universe itself? His questions are how a poet, an intellectual, the forger of the uncreated conscience of his race no less, should behave. This is the dimension lent it by the third person, one that would disappear if we were to transcribe Portrait entirely into the first person of its final diary entries. For the Wake, too, the Kane-like fantasy is everywhere in the first four chapters in particular, as they endlessly stage that unanswerable question of how the world seems to the unconscious, troubled sleeper.

But classical narrative theory has lots of trouble with impersonal narration. Everywhere, it rushes to fill in the void by inventing personlike “narrators” who can be supposed to know, or see, what we are being told. It may be worth resisting this rush, to consider what might be at stake in the possibility of an impersonal dimension to narration. We have that, certainly, with Finnegans Wake, where there’s barely anything like an “I” to connect all of this to. But don’t we also have it already in, for example, the very common use of third-person narration focalized on one of the characters? Take A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, for example. Doesn’t the third person there work not as the point of view of some impossible, magical being with access to Stephen’s inner life, but as an aspect of Stephen himself, this proud, idiosyncratic boy and adolescent who is always viewing himself as if seen not quite by others (for whom he often has a complete disdain) but by the universe itself? His questions are how a poet, an intellectual, the forger of the uncreated conscience of his race no less, should behave. This is the dimension lent it by the third person, one that would disappear if we were to transcribe Portrait entirely into the first person of its final diary entries. For the Wake, too, the Kane-like fantasy is everywhere in the first four chapters in particular, as they endlessly stage that unanswerable question of how the world seems to the unconscious, troubled sleeper.